I picked up this book a few days ago with the vague sort of feeling that I wanted to read something a little different. It was somewhat frivolous as I have a mounting pile of tempting books that I am itching to read, but somehow this one has queue-jumped.

I picked up this book a few days ago with the vague sort of feeling that I wanted to read something a little different. It was somewhat frivolous as I have a mounting pile of tempting books that I am itching to read, but somehow this one has queue-jumped. This story of a deformed young spanish boy, Bartolomé, is inspired by the painting 'Las Meninas' by Diego Velazquez, who painted in the court of King Philip IV in the 17th century. Velazquez regularly painted the royal family, especially the king's little daughter, the Infanta in question.

'Las Meninas' now resides in Spain's national art museum, the Prado in Madrid, and you can view it here: www.museodelprado.es

The original children's novel by Rachel Van Kooij was first published as Kein Hundeleben fur Bartolomé, byJungbrunnen Verlag in Vienna, a decade ago. But freshly translated by Siobhan Parkinson, we are now able to enjoy it in our mother tongue, here in the UK.

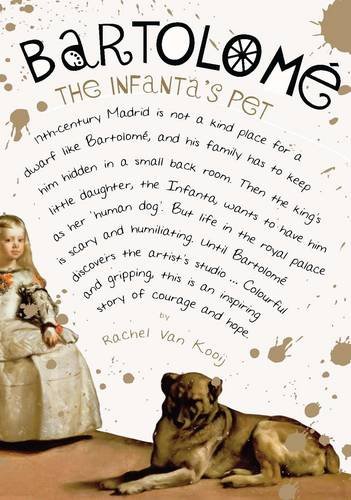

Apart from being an interesting story, the physical book itself is very diverting. It's unusual to see a book with its blurb written on the front, and quite refreshing to see a publisher break the mould and play with an accepted order. The front cover gives us all we need to know to want to read the book, with a clean, strong design and an appealing handwritten block of curving text that invites us into Bartolomé's world. The paint splodges in raised, shining gold are delectable and give us a taste of the expressive nature of our little hero.

Part of the famous painting is generously spread around the spine and back cover, providing a visual anchor for the reader in the rich setting of royal Madrid.

Another enterprising effort from Little Island, is their success at securing funding to support the book's publication. Grants were given by the Goethe Institut in Germany, the National Lottery, through the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, the Ireland Literature Exchange, and the Bundesministerium fur Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur, Vienna, which is something to do with art and culture. Hurrah for all of them. It's really really hard for publishers to survive and flourish, and for artists and writers to make a living, so it's encouraging to see something creative being supported in this way.

I haven't quite finished reading Bartolomé, the Infanta's pet, but I am riveted to its every word. I've been sceptical about translations in the past, and worried I'm not getting the real deal if I'm not reading a story in the language it was created for, but I am increasingly understanding that a translator is as much of an artist as the original author and I have come to appreciate their voice through the story.

It's tricky, at first, to juggle these characters around Bartolomé, and understand their behaviour and perspectives. The era is one thing to get your head around, and the way married couples related to each another. The way a wife submitted to her husband, unquestioningly. The inequality of things. The expectation on a young girl to marry early. The power of a man over his household. And then there is the huge issue of the way Bartolomé is treated by his family, by his village, and by society as a whole. The inhumanity is disgusting and unbelievable. It would appear that his mother does love him, but not strongly enough to stand up for him, or even to show much affection. His siblings on the whole, don't have a lot of time or sympathy for him, and everyone is ashamed to be seen with him.

In every situation Bartolome is given the least affection, the least food and comfort, the least praise. His life is blighted, not by his own deformity but by the lack of opportunity, hope and love around him. Despite his circumstances though, he is ever eager to please and always appreciative of any small break in monotony or misery.

The family are poor and uneducated but Juan, the father, has work - tending to the King's horses. Eventually, Juan is given permission to collect his family from rural Seville, to live with him in a basic flat. While the family travels to Madrid on foot, with a small cart of furniture to start their new life in the city, Bartolome is confined to a small wooden chest to avoid being seen. Cruelly, Juan keeps him hidden until they are in the confines of their apartment and Bartolomé is forbidden to show himself outdoors. Juan barely tolerates Bartolomé's presence and at the earliest opportunity dismisses him to a new life as the Infanta's plaything.

In this story of courage and unlikely hope, Bartolome shines through the degradation to prove his worth to those who would persecute.

As ever, the quest for kindness and love is one worth persevering for.

No comments:

Post a Comment